In the Paintings Together【Parent-Child Reading Guide】

點閱次數:947

Liao Chi-chun (1902 – 1976) was born to a poor family of Koroton, Taichū-shū (now Fengyuan, Taichung). The father was often absent, and Liao had to help out at home. At age 8, he entered the town’s Taiwanese-only primary school (kōgakkō). During this time his mother died unexpectedly, but Liao carried on the education with his brother’s support.

That Liao’s mother was an embroideress may have inspired Liao to take up doodling. He drew on empty spaces in the household ledger. To buy pencils, he peddled Taiwanese cruller (iû-tsia̍h-kué, youtiao or oil stick) on weekends, while carrying his little nephew on the back.

Liao graduated from primary school in 1916 with honors. He was then admitted to a two-year advanced program, an uncommon feat for a Taiwanese. The program qualified him for the Governor-General’s National Language School (later renamed Taihoku Normal School) in 1918. The tuition-free school was where the Japanese trained teachers in the colony, its campuses and buildings housing pedagogical institutions to this day. As a schoolteacher, Liao would be secure in terms of both income and social status.

Liao aspired to oil painting but did not at first understand how it worked. For a while, he practiced using paint on cardboard, until he learned from Japanese students nature sketching in Taihoku New Park (now a park commemorating the February 28 incident) what paint tubes looked like and how the pigments were supposed to be applied to the canvas. Hence he began saving, and asked acquaintances to bring oil paints and painting tutorials from Japan.

Lin Chiung-Hsien, Liao’s eventual wife, came from a prominent Koroton family. The Lins were Presbyterian; Lin Tzu, Chiung-Hsien’s father, was a benefactor to less fortunate townspeople like the Liaos, while Lin Chao-chi, one of Chiung-Hsien’s brothers, was a pioneer in Taiwanese geological research. Gifted, determined, and well-read, Lin once tore apart a second-prize certificate in public for she refused to believe that a Japanese peer ranked above her on merit and not racism. When Liao proposed, she accepted on one condition: that Liao obtain a degree from Tokyo Fine Arts School (Biko, now Tokyo University of the Arts). In her eyes, Liao’s talent was undeniable. For the rest of their lives, Lin supported and accompanied Liao in his artistic pursuit.

Liao boarded the ship to Japan on March 22, 1924. To make her asthmatic fiancé more comfortable, Lin bought a second-class ticket without his knowledge. Liao wondered on the journey as to why there were so few fellow travelers; he only realized that it was a treat from his fiancée when he saw hordes of people coming out of the lower decks at the Port of Kobe. Armed with this act of love, Liao passed Biko’s entrance exam without a hitch.

Among the third-class passengers on the same ship was Chen Cheng-po (Tân Tîng-pho), a senior to Liao at Taihoku Normal School. Chen and Liao ran into each other on the dock, prepared for the exam together, and both chose Western painting as their area of study.

En plein air was the mode of instruction and creation at Biko during the 1920s. It begot a style capturing Impressionist light without sacrificing academic realism, such as clear contours. Most of Biko’s faculty, however, were quite liberal. For instance, Tanabe Itaru, an European-educated professor who paid special attention to the Taiwanese pair, refrained from enforcing his style on them and encouraged Chen and Liao to each develop their own. One could barely notice the influence of Tanabe in Chen or Liao’s mature works, or that Chen and Liao were once classmates.

Liao took a break from Biko to marry Lin in Taiwan on July 19, 1925. He returned to his studies soon after, paid for by Lin’s salary as a kogakko teacher. In 1927, Liao graduated and moved with Lin to Tainan, where the latter opened a stationery store called Bungeisha to earn a living and to more readily acquire supplies for the budding painter. There could simply not be Liao the master without Lin managing his day-to-day affairs and giving him the space to create.

In Tainan, Liao was hired to teach fine arts at the private Prebyterian High School (now Chang Jung Senior High School) by Lin Mao-sheng, the Chair of the school board. The first Taiwan Art Exhibition (Taiten) was also held that year, marking a major step of the local art scene toward an alternative vision to the all-Japan Imperial Art Exhibition (Teiten). In any case, just to be included and able to show your work at either exhibition meant you were an artist commanding respect. Liao’s Female Nude and Still Life were displayed at the first Taiten, with the latter awarded a special prize. Courtyard with Banana Trees (1928) and Landscape with Coconut Trees (1931) were selected into the ninth and twelfth Teiten, respectively. Given all the achievements, it was no wonder that Liao was made juror at successive Taiten from 1932 to 1934.

Besides composing his own works, Liao strove to bring the latest artistic ideas to Taiwan. He formed the Red Island Society with Chen Cheng-po, Yen Shui-long, Yang San-lang, Li Mei-shu, and other like-minded Taiwanese, to discover native art, hold exhibitions, and to elevate the public’s taste and culturedness in general. The society expanded and became Taiyō Art Association in 1934, crowning an era of openness and enlightenment in the colony.

After a series of teaching jobs, Liao landed tenure at Taiwan Provincial Normal College (now National Taiwan Normal University) in 1947. He was a serious professor beloved and looked up to by the students. What he learned and experienced in Japan, he passed on to them. His students grew to be a diverse cohort, unbeholden to labels and criticism. At Liao’s urging, they formed the Fifth Moon Group ten years later, the first painters’ organization in Taiwan dedicated to modern art and one of many that followed and moved Taiwanese art forward.

When Liao first took up the brush, he could be classified as an Early Impressionist transcribing objective inspiration. He experimented with Late Impressionism, Fauvism, and Abstract art later on, becoming more and more comfortable expressing his subjective feelings in response to scenery, an object, or a human figure.

Courtyard with Banana Trees, the work that made Liao’s name, depicts the back alley of his then lodging in Tainan. There are his neighbors doing chores, as well as delicate modulations of light and shadow. Green Shade, which was displayed at the 1932 Taiten, showcases the more tropical and exotic summer of Taiwan. Liao went nature sketching with Ryuzaburo Umehara at Taiwan Confucian Temple and Fort Provintia when the latter was invited to judge the 1933 Taiten. Liao was deeply moved by Umehara’s free strokes and fiery colors that turned sketching into an act of landscaping, and began adopting red, yellow, blue, white, and green—bright, bold Eastern colors that could be found on traditional buildings in Tainan—in his Western paintings. In the 1950s, he turned his attention to Abstract art, forsaking outer visuals in favor of a direct window into inner sentiments. On the US State Department’s invitation, Liao visited American and European museums of fine arts in 1962. The tour deepened his understanding of contemporary Western Abstractionism, which he re-interpreted into a unique style of his own. The concern of the modern painting, he thought, was not being abstract or realistic, or being figurative or non-figurative, but to be of substance and expressiveness, and, most importantly, to awaken beauty in the beholder. Liao hoped that his creations, like Sundays, would bring people peace. His works from then on are thus characterized by vivid yet harmonious colors arranged in a semi-abstract style.

Liao had been a vanguard throughout his career. He was ever the pure, ingenuous soul pouring onto the canvas and sharing with family and friends his love for art and Taiwan, unaffected by outside interference.

In the midst of the chaos after the World War II, Liao served briefly as acting principal of Tainan Prefectural Second High School. The Japanese were evacuating, and the assets they left behind were often illegally taken over without retribution. Instead of taking advantage of the situation, Liao and son moved quickly to paste official ownership notes on the buildings, thereby saving much of the school, while he and his family stayed on in a meagre house as before.

The aftermath of February 28 incident, 1947, took away the lives of Chen Cheng-po and Lin Mao-sheng, two of Liao’s best friends. For a while, he fell unusually silent, and unable to pick up the brush. That was the hardest time in his life. He finally moved on, returning now and then to paint at those friends’ haunts to honor them.

Besides sketching en plein air and drawing landscapes during and after the tour of the West, Liao most often painted his family and home, attesting to his gratitude and love toward Lin and their children. Lin admired his art and often offered constructive commentary; in return, Liao gave her gentleness, warmth, and laughter. Liao Chi-Chun claimed to have appeared together with the children in his paintings, meaning they could always feel his presence through the frames. Lin Chiung-Hsien also took Liao’s students, especially those with difficulties, under her wing. The couple, with their artistic love, was a testament to the Christian faith, and shall be remembered for generations to come.

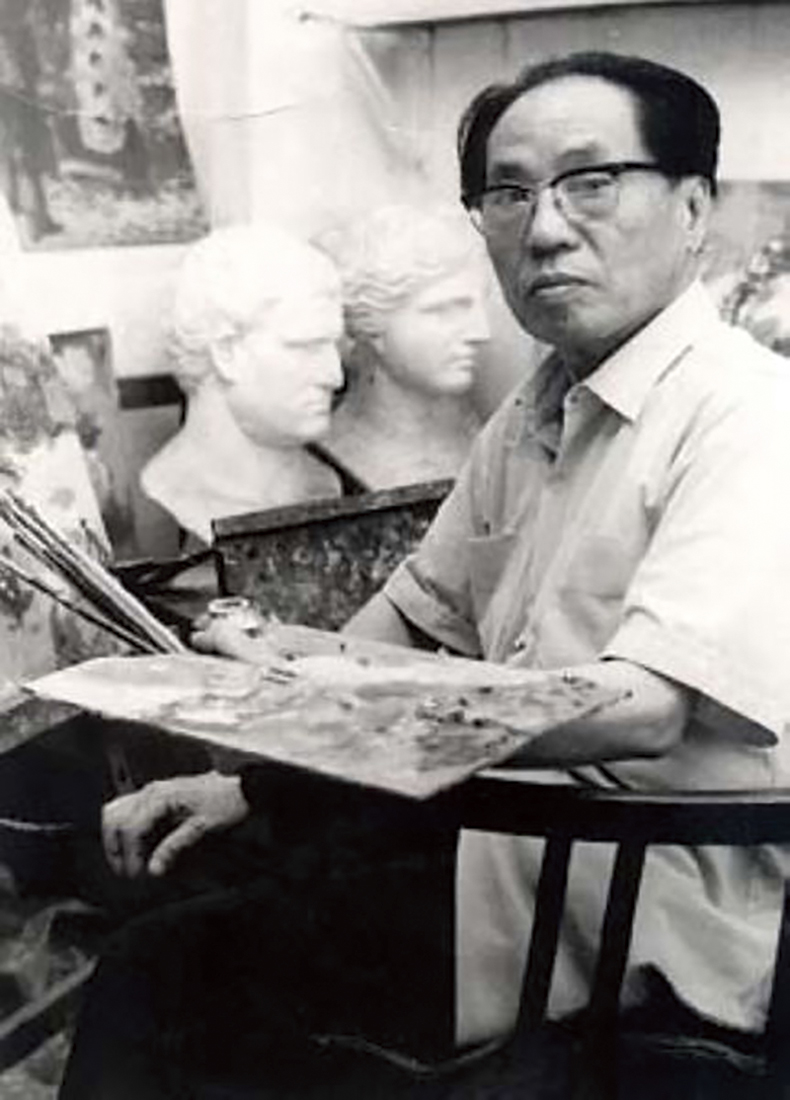

Liao Chi-Chun and his family.

The author would like to express his gratitude toward the Liao family for their input during the creation of this book.